The “Male Gaze” With its Discourse on Ideology Interpellation and Media Internalization

In this exhibit, I’ll be exploring Corinn Columpar’s tracing of Laura Mulvey’s contribution to the “Male Gaze” theory, using Marvel’s Black Panther as a point of illustration. While Columpar draws from a number of different fields, the discourse explored today will be in tandem with film studies and feminist theory. The purpose of this exhibit is to focus on the ideology that suggests the “Selfie” as a form of self-oppression. This draws from J.B. Brager’s scholarly work “On the Ethics of Looking” (2017) in relation to the political frameworks of hyper-visibility, erasure and misrepresentation (162). For film studies, focus will be directed towards to how media and technology construct our sense of self and how we understand the “male gaze” through Louis Althusser’s concept of ideology interpellation. By establishing an understanding of the production, distribution and consumption of “Selfies”, one can orient themselves to a deeper understanding towards the value that spectatorship provides. After this, a basis will be established for film studies and how the psychoanalytical discourse brought about by spectatorship in the context of the “male gaze” could be influential in tandem with Levi-Strauss structuralism and gendered binary opposition. The purpose of this contrast is to emphasize the duality, which Columpar highlights in his work surrounding fetishistic scopophilia and sadistic voyeurism.

Critical Overview of Political Frameworks of Visibility

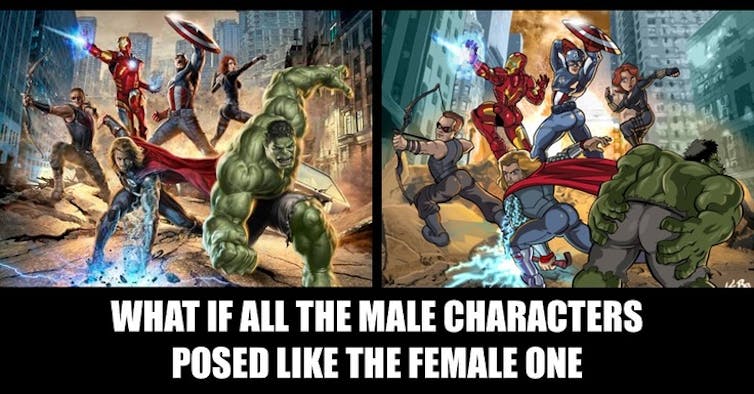

Louis Althusser’s concept of ideology interpellation is the defined through Marxist theory as a process in which we interact with a culture’s ideological value and internalize it. This is significant to begin with as we explore Laura Mulvey’s emphasis on the heterosexual, masculine gaze that sexualizes women for the male viewer, posing a potential internalized threat of fantastical projection. It’s the idea that as someone might fantasize, they would expect that out of the world they participate in. Since this is an internalization, it’s important to distinguish the concepts that would contribute to this threat. Fetishistic scopophilia is a strategy in which the “specularized woman is made reassuring through hyper-glamorization” (28), sculpting an ideological version of women that, alone, seems purely for the sake of fiction and/or inspiration. However, in tandem with sadistic voyeurism, which entails the “investigation of a female character by a male representative of the Law” (28), the psychoanalytical discourse becomes a cautious worthwhile amount of attention.

By iconizing the idealistic woman, the male gaze evokes an embedded anxiety with castration. This draws more from the sadistic aspect of sadistic voyeurism, considering the two options posed for a male with a sadistic outlook on the idealistic woman. It’s either, as Mulvey describes, the “preoccupation with the re-enactment of the original trauma (investigating the woman, demystifying her mystery)” (11) which is usually counterbalanced with a greater inner discourse, encompassing devaluation or punishment riddled with guilt. Columpar draws an important detail in regards to male anxiety, and it’s built off this core idea that males use the idealized image of female perfection to motivate themselves. Mulvey writes about the “determining male gaze [that] projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly” (33), and how this can be an engagement of an internal conflict surrounding the potential of rejection and castration. When it comes to our illustrative example Black Panther, this is explored in detail by Thomas Piontek.

Film Studies – Another Lens

The male gaze is explored in the context of “spectatorship”, which is essentially a modality in which the spectator can become involved and understand the inner workings of something without really getting involved. While Piontek draws on the fact “There’s no ugly men in Wakanda” speaking to the nature of it being, as Lauren Levitt is quoted within Piontek’s work “a mode or aesthetic…in which people or things are appreciated because of their artificiality, exaggeration, or theatricality” (173). In the context of attractive men being in a camp, it sets up a film perspective that’s popular for sexual spectatorship. The idea behind tribes, families and work in one place, intimacy and bravery, which may go more hand in hand than we would assume. When it comes to film and media, the psychoanalytical discourse that Mulvey explores through objections of sexual stimulation and Levi-Strauss structuralism highlight the intricacies that are embedded in gendered binary opposition. For instance, Mulvey suggests that the binary is not neutral but charged in its potential assignment of power. Levi-Strauss suggests that the assignment is by nature, but Mulvey follows that it’s through culture. The internalization of power as mirrored from our individual experience becomes a vital paradigm in which a healthy effect of sexual stimulation can be gaged. When their appearance is coded for a strong erotic impact, the line of motivation and intention gets blurred. The distinguished sexualization of the male body ensues in the scene where Killmonger undresses before fighting T’Challa for the throne, having the camera work and makeup art on his body (dots symbolizing his kill count) pulled attention towards his physique. Thomas Piontek writes on how these action movies and superhero films mainly share a viewership demographic of straight, male audiences, and by erotically charging the fetishistic scopophilia involved with eroticized masculinity, the film runs the risk of derailing normative heterosexuality.

Piontek draws on the historical justification of a “transparent narrative pretext” (Hunt, 70), showcasing feats of strength and allowing for non-sexual physical contact between male characters in an attempt to establish power. The establishing of power is an intricate dynamic to dive into since it encompasses a plethora of signals and symbols that communicate its presence, and idealized masculinity is one of them. This doesn’t necessarily mean that it can only be idealized masculinity as power can also be established through leadership and rejection of the norm, which are not exclusively gendered. It’s important to return to Althusser to deeper drive the significance of these influences. Through ideological interpellation, the emotional capacity of spectator’s is drawn from the shifty process. Althusser cites this “immanent or latent structure of the dissociation of times…” (6) to detail a bit more of the inner workings of the silent crowd that a spectator will likely be a part of. It’s by the defaulting, which would be a discrepancy to external reality more or less if one dissociates enough, this would extract a sense of involvement on the spectator’s side. Put simply, the depth of “relatability” is like a plague on man’s perspective, and if he is righteous in his male gaze by his own frame of mind, it would seem to him that it’s the nature of life itself. Yet, it’s evident in his conflict and emotional friction that his capacity to drop his male gaze and embrace a deeper sense of humanity by connecting, involving and elevating his awareness of life beyond himself, greater insights are achieved. Now, as explored beforehand, this is not necessarily gender exclusive, but for the sake of illustrative example and frequency, the male gaze does pose more of a psychoanalytical threat than women. It is by nature of power dynamics and embedded rationalizations that a heteronormative and mostly homogenous societal framework might provoke, cultivating what Althusser describes as a “non-relationship that is the relationship” (6).

While Thomas Piontek’s work does drive heavily on the issues revolving the LGBTQ+ community and Black Panther, it does help illustrate the context in which political messages are threaded. It’s also an important detail that the premise of his work is based on the original literature having queer representation that the film did not introduce, leaning into what Piontek calls “queer erasure”. There’s a lot of gendered nuances, for instance, masculinity is not iconized by the “disliked other”, or particularly feminized individuals. The woman of Dora Milaje are expressive of their fierce strength, far from gentle and small. Their choice of clothing doesn’t lean into sex appeal, their fierceness is vivid and emphasized. While the men of Wakanda are highlighted by their “voyeuristic and fetishistic pleasures” (Piontek 701), the film does lean heavily into a celebration of Afrocentrism by making a point to emphasize it’s beauty and brilliance. The absolute absence of white narrative and presence gave a racial lens in which to approach the gaze within the film, especially since the erotically charged characters were mostly men through their fetishistic apparel. Nonetheless, Piontek’s work highlights the nature of politically charged takes on representation within film, citing a columnist that claimed “when LGBTQ+ critics call out Black Panther‘s lack of a queer plotline, they’re putting themselves before the liberation of Black people” (685). Piontek does go on to showcase how problematic of a claim this is, but its significance does have its roots in the original ideological concept of the male gaze and how contested it is within the threads of society.

Selfies, Consumption and Concluding Hyper-visibility with the Male Gaze

As you can see, the framework in which visibility and film studies are situated in pose a contemporary question towards the “Selfie”. J.B. Brager’s “On the Ethics of Looking” (2017) explores key questions in regards to “where we are looking from, as well as who we are looking at, within political frameworks of visibility, hyper-visibility, erasure and misrepresentation. “(162). This allows you to orient yourself based on the representational discourse and see what isn’t there. Many, if not most, gaze upon media and see what is there, but it takes a critical mind to see what isn’t. With selfies, there’s a hyper-visibility that internally can be seen as a fixation on what is and isn’t there, which can be a difficult psychoanalytical process depending on a whole array of factors. When it comes to viewing selfies of the other gender (remember, not exclusively binary but for the sake of this hypothetical), the male gaze is no longer neutral but charged in the same potential assignment of power that was detailed before. It’s then by understanding the intention behind production, the mental framework in which distribution is done (i.e. the addiction to feedback loops, likes and comments), the consumption becomes a fast food machine that warrants a cause for concern.

The male gaze isn’t inherently troublesome, since it is part nature and part nurture, yet in the context of its subconscious power and influence, it’s important to evaluate one’s insight and understanding of their worldview, especially over the psychoanalytic discourse you might participate in. Whether it be through the instrument of film, media images at large, or just a skewed narrative that’s preset to adopt your point of view, it’s important to take a critical approach to grasp the visual culture that you would’ve missed otherwise.

© Copyright 2022 Tristan Jones Ryerson University

Images in this online publication are either in the public domain or are being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.

Works Cited

Brager, J B. “On the Ethics of Looking.” Selfie Citizenship, 2017, pp. 161–163., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45270-8_17.

Columpar, Corinn. “The Gaze As Theoretical Touchstone: The Intersection of Film Studies, Feminist Theory, and Postcolonial Theory.” Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 1/2, 2002, pp. 25–44, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40004635. Accessed 20 Apr. 2022.

Étienne Balibar; Althusser’s Dramaturgy and the Critique of Ideology. differences 1 November 2015; 26 (3): 1–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-3340324

. “What Are Big Boys Made Of? Spartacus, El Cid and the Male Epic.” You Tarzan: Masculinity, Movies, and Men, edited by Pat Kirkham and Janet Thumim, St. Martin’s, 1993, pp. 65–94.

Mulvey, L. (1989). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In: Visual and Other Pleasures. Language, Discourse, Society. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-19798-9_3

Piontek, T. (2021), “There Are No Ugly Men in Wakanda”: Black Panther, Spectatorship, and the Queer Male Gaze. J Pop Cult, 54: 682-706. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/10.1111/jpcu.13045